Mmm, fresh eyes. There’s nothing like the smell of fresh eyeballs in the morning: Smells like finding all the mistakes.

Today’s Shelf Life is about a very simple premise of editing and publishing, and about how to put that premise to work for you. The very simple premise is: Fresh eyes spot things that jaded eyes do not. Imagine having jaded eyes. I have green eyes so I basically do. It’s rad.

Eyes that are new to a text will see mistakes that familiar eyes miss. This is a solid fact of proofreading. The more familiar you are with a text, the less likely you are to spot mistakes in that text—even if you are looking for them.

The human brain is made to take shortcuts. The human brain is the busiest and also the laziest organ in the body. The brain just has so much to do, it must take shortcuts. Otherwise it would never get everything done and one of its responsibilities is making you breathe so—the brain can’t slack off. If the brain slacks off and you stop breathing and the meat mech dies, brain dies too.

This is just science. This is what you learn in science editor school.

The human brain relies on pattern recognition to get its job done efficiently. Pattern recognition—the ability to identify patterns in the environment and extrapolate information from them—is integral to our day-to-day functioning. It’s how we know when it’s safe to drive through an intersection versus when we must stop. It’s how we identify which of our fellow humans are safe and which are potentially dangerous. It’s how man historically has recognized large predators hidden in the tall grass.

It’s also messing up your proofreading but there’s ways around it and I’m going to help you out with those ways.

What I mean by it’s messing up your proofreading is this: When you’re proofreading something you have written yourself, your brain recognizes patterns of words. These patterns are familiar: After all, you wrote them and have probably read them several times since. Your brain sees a way to speed up the reading process. Just as your cell phone predicts (badly) what text is to come next when you’re typing a text message, your brain will begin to predict the words that are coming next when you read familiar text. Instead of reading the whole word to make sure you have it right, your brain might read just the start of the word and fill in the rest to save time. Or it might even skip over words altogether if it knows what’s coming.

From your perspective, though, you’re just reading. You don’t realize your brain is doing this. If you’ve ever noticed that you can read your own work faster than you can read someone else’s—I regret to inform you it’s not because your work is so much more engaging than theirs. It’s because your brain is taking shortcuts.

Circling back to the concept of jaded eyes, I chose this term carefully. I don’t simply mean eyes that are tired, or eyes that are familiar with something, but specifically I mean eyes that are tired and a little bit bored from familiarity with something they are reading.

Let me be clear: Tired eyes miss things. Bored eyes miss things. Familiar eyes miss things. Tired, bored, familiar eyes miss more things.

From the above premises arise some conclusions:

It’s best to choose a proofreader for your work who is not yourself.

Ideally, your proofreader is not the same person as your copyeditor. Although some of us have both skills, a proofreader who is new to your text has fresher eyes for the work.

The parts of your project that are most visible (cover, title page, table of contents, running heads, pagination) should be seen by the most different sets of eyes.

These bullet items are publishing-company best practices. Every junior production editor learns this during week one when a harried senior editor drops something on their desk for a second look “just to get some new eyes on it.” Even if the junior editor is too new to have honed their proofing skills to a fine point, they could very well see something the seasoned senior editor has missed because the senior editor has probably already looked at it ten times.

As a junior editor, few job moments are more rewarding than spotting something a senior editor has missed.

But if you’re the writer, you may not have the luxury of proofreaders and copyeditors and senior editors and junior editors and extra eyeballs. You may just have yourself and your own two eyeballs and no budget to speak of. Maybe you’re preparing your query letter for an agent, or preparing your book proposal for an editor, or preparing your manuscript for self-publication, and you need the material to be correct an error free. But you wrote it yourself and then read it at least a dozen times to perfect it—how can you approach the text with fresh eyes?

Here are five strategies you can use to find those last lingering typos, grammatical mistakes, and other errors in your text even when your eyeballs are completely jaded.

Listen to It

The hands-down best way to read your own work with fresh eyes is to read it with your ears. Even if your eyes are jaded, your ears aren’t. Listening to your own work will help you find all the mistakes and you might also be surprised how many bits of the prose or dialogue jump out at you as clunky, imperfect, or just “not how you meant them to sound.”

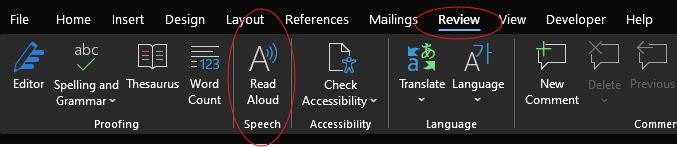

To listen to your own work, you can use the text-to-speech reader that many word processors have built in. For example, in Word you navigate to the “Review” tab and then to the “Read Aloud” button:

Not a Word user? No problem: Download the free Speechify browser extension to read your document to you from any web browser.

Read It Aloud

No time to deal with a text-to-speech engine? The next-best thing is to read your work aloud to yourself. This option is frankly not as good as using a screen reader to read the text to you because your brain will still try to implement shortcuts and you risk reading a sentence aloud the way you meant it rather than the way you wrote it. Still, reading your work aloud to yourself will turn up plenty of mistakes, errors, and less-than-optimal wording that you may have missed when reading silently to yourself with your eyeballs.

A nice compromise measure is to have another human being read the text aloud to you. I still think this isn’t as good as using a screen reader because human inflection can go a long way toward obscuring your writing mistakes, whereas a screen reader will just lay them appallingly bare. But if you can’t do a screen reader for whatever reason, having another person read to you or reading aloud to yourself work, too.

Take a Break

If you can afford to give yourself the gift of time, stick your work in a drawer for two or three weeks to let your eyes rest and un-jade. The longer you can look away from your manuscript, the better. If you can write something else in the meantime, or even read something else substantial, that’s still better. All this serves to defamiliarize your eyes and brain from the work so you can come back to it a little fresher.

Read It Backward

When all else fails, read backward. Start at the end of the manuscript, with the last paragraph. Read that paragraph start to finish. Move up to the penultimate paragraph. Read that one. Then the third-to-last paragraph. And so on.

When you read your text backward this way, you prevent yourself getting caught up in the flow of the story, plot, and dialogue. Each paragraph will stand alone since you’re not reading them in a logical first-to-last order. It’s way easier to focus on scrutinizing one paragraph at a time than the whole book in sequence.

Borrow a Friend

Finally, if you can swing it and the ask is not huge, see if you can get another human being to read the most-important, most-visible elements. You might not ask them to proofread an entire book manuscript, but if you’re dealing with a query letter or book proposal, asking a friend to do a quick, free proofread is quite reasonable.

If you do have a whole book, ask your friend if they can just check the major elements for you: Can they proofread just the front cover, back cover, and spine? Could they proof just the front matter? Could they page through the proofs and just do a check that the pages are all in the right order? These are the type of errors that jump out at readers and make them ask “Gosh, didn’t anyone proofread this?” If you can eliminate those errors before going live with your content—do it.

If you have questions that you'd like to see answered in Shelf Life, ideas for topics that you'd like to explore, or feedback on the newsletter, please feel free to contact me. I would love to hear from you.

For more information about who I am, what I do, and, most important, what my dog looks like, please visit my website.

After you have read a few posts, if you find that you're enjoying Shelf Life, please recommend it to your word-oriented friends.