Today I bring you a topic that never even made it onto the editorial calendar because the idea was filed under “no one knows about this but no one cares.” It’s probably better if you don’t have the information contained herein. You don’t need it, trust me. Some people want it, though, for reasons I don’t understand, even though they certainly don’t need it.

I found myself answering a question recently about interfacing with the Library of Congress as a person who is self-publishing a book, and I will spend some time expanding that answer in today’s article so next time someone asks about it I can go, “Oh hey I wrote a thing about exactly this.”

First let me spin you a yarn about my very first day at my very first publishing job, because I know you have all the time in the world this morning.

I graduated college off-cycle in December and started half-heartedly looking for a job in January, mostly resigned to taking a semester off looking for a job and then starting a six-month teacher certification program at the local community college, because there’s not much else you can do with an undergraduate degree in the local language everyone already speaks.

My mom worked out of an office in our home (way before telecommuting was a thing), but one nasty cold day that January there was some unexpected emergency and she had to go to her actual, physical office in Northern Virginia. She drove to the closest Metro station where somebody handed her a copy of the now-extinct paper The Express (real ones know the paper I mean), which she read on the train. It contained a help-wanted ad for an editorial assistant at a publishing company five minutes from where I was living with my mom at the time. I applied, interviewed, heard not a peep for a month, and then got a call in mid-February to start immediately.

Serendipity.

I arrived in an actual suit, the same one I wore to the interview—in fact, my only suit—but with a red blouse (“a power color,” said my mom) instead of a white blouse underneath, to make it a different outfit. In hindsight I can’t remember why I thought it was advisable to wear a suit. I filled out HR paperwork and was shown all of the important publishing equipment and facilities (coffee maker, bathroom, building exit approved for smoking) and then my cube.

I was given the company’s login and password to the Library of Congress publisher account and briefly shown how to apply for “CIP data” for a forthcoming manuscript. When the trainer was satisfied that I understood how to fill out and submit the application, a pile of ten fresh manuscripts was placed on my desk. I prepared documents and filled out CIP applications for nine hours straight and went home and told my mom I would not go back the next day even if it meant I spent the rest of eternity flipping burgers.

Mom convinced me to go back and try it for one more day and they gave me some more interesting work to do, the rest is history, and I learned a valuable career lesson, which is to start new employees on Tuesdays. No one feels like onboarding on Monday mornings. That’s the actual useful information from today’s article: Onboard on any day other than Monday when possible.

During my time there I did a lot of intermediary work between the publishing company and the Library of Congress, primarily in the form of CIP data applications and copyright registrations. I’ve processed hundreds of applications for CIP and PCNs and registered hundreds if not thousands of copyrights. So today and Thursday I am sharing this knowledge of this tedious process to answer all of the self-publishing author’s Library of Congress questions, like

What is CIP data?

What is an LCCN?

How is an LCCN different from a PCN?

Do I need any of those things?

How and when do I get any of the above for my book?

What does any of this have to do with my copyright?

The shortest answer is, you don’t need to get or do any of this stuff. If you’re going to work with a traditional publisher, there is no point in trying to interact with the Library of Congress because your publisher will do it for you. If you’re self-publishing, you still don’t need to do or get any of these things but you can if you want. I’ll walk you through what they are, why you might want them, and how to get them.

One of the most common snide insults publishing people lob at poorly produced books and manuscripts—I know this is uncalled for and mean—is, “Has this person ever seen a book?” I have seen all sorts of wild stuff. Books published with pagination completely wrong. Books published with folios falling into the gutter. Books prepared with just . . . no attempt at front matter. Books where the title on the cover is completely different from the one on the title page. Has the person who prepared this ever seen a book? Even once in their life? Or did they just imagine what a book might be like and go from there?

On the extreme opposite end of the spectrum, one of my fondest publishing memories in my entire career was receiving a manuscript from a most scrupulous first-time author who had clearly studied several books while preparing their manuscript. They had personally created:

A praise page with endorsements solicited from their friends and family

A half-title and full title page, complete with our company’s name and our logo pasted at the bottom

A copyright page complete with a CIP data block they had made themself

I’m not being condescending about this. The author clearly cared very much about making sure they had supplied everything we might need to make their book a success. I kept their carefully prepared homemade front matter pinned to my cube wall for a long time.

Okay at this point it would probably help if I explain what “CIP data” actually is. If you open pretty much any book and turn to the copyright page, you will see something like this:

The block of information I marked was provided to the publisher by the Library of Congress. It’s the “cataloging in publication (CIP) data.”

One of the functions of the Library of Congress is to catalog books that publish in the United States. A book comes out, and at some point—theoretically—someone who works at LoC in the cataloging group will review the book, read some or all of it, and then catalog information about it. As you can see, the CIP data block contains metadata about the book (title, author, publisher, ISBNs), a summary of the plot, category headings, Library of Congress Classification identifiers, and Library of Congress Control Numbers (LCCNs).

The purpose of these data is to help librarians in the United States (and, secondarily, booksellers) understand how to catalog a book when they receive it into their collection.

At some point, LoC decided to begin cataloging books while they are in publication, meaning, books that have not published yet. The publisher, upon receipt of a new manuscript, logs into their account and uploads part of the manuscript, fills out an application, submits it to LoC, and in six to eight weeks receives the CIP data. The publisher then places the data they received on the book’s final copyright page to facilitate librarians and booksellers accessing the information when they need it.

The LCCN—the unique key that the Library of Congress assigns to each book that has a record with them—comes as part of the CIP data block, but requesting and receiving CIP data is not the only way to get an LCCN. This is good news for you if you’re self-publishing, because self-published books are not eligible for the CIP program. The LOC makes this clear in several ways:

If you paid for your book to be published, your book is ineligible.

If the book is published on demand, it’s ineligible.

Unless the publisher has published at least three books, by three different authors, all of which have been acquired by at least 1,000 libraries in the United States, the book is ineligible.

In short: If you’re self-publishing or vanity publishing your book, you can’t get CIP data.

CIP data exists to help libraries catalog books, so LoC doesn’t offer this service to books unless they are likely to be “widely acquired” by libraries. Libraries are about as likely to acquire a self-published book as a bookstore is, which is to say, they are not (likely). Not impossible, but unlikely. If it’s a goal for you to have your book on library shelves (and/or brick-and-mortar bookstores), you should exhaust other publishing options before deciding on self-publishing.

If you have high hopes that your self-published title will ultimately find its way into libraries anyway, you may want to apply for a pre-assigned control number (PCN). A PCN is the same thing as an LCCN. A PCN is simply an LCCN that is preassigned, not assigned as part of the CIP data creation process. They are both Library of Congress Control Numbers.

There’s a little bit more wiggle room on who can apply for a PCN versus who can apply for CIP data. The Library of Congress still considers self-published titles to be ineligible, specifying that applicants must have a place of publication and an editorial office—both in the United States—the latter of which can answer questions about the book if needed. But, listen, it’s not hard to set yourself up as “an official publishing company” operating an editorial office out of your home if you really want to do this.

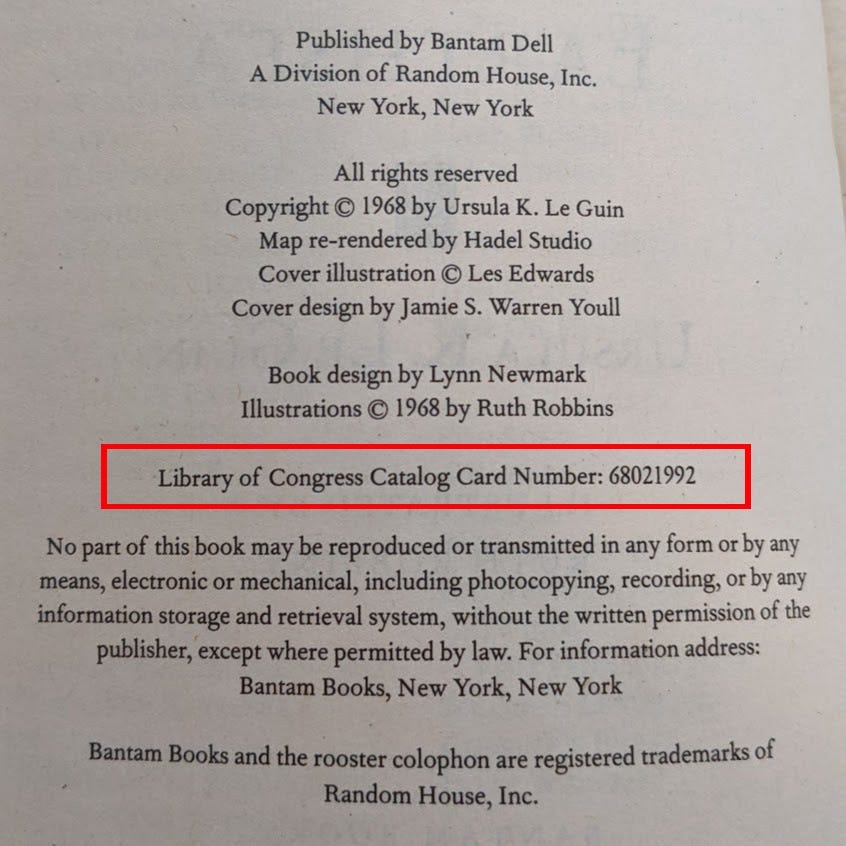

With a PCN, you fill out an application with the book’s metadata but you do not upload any part of the manuscript with the application, as no one will be reviewing the application to provide detailed cataloging data. Instead you will receive a PCN, which you can print on your copyright page like so:

Wow, why wouldn’t Bantam do a full CIP app for Ursula Le Guin?! Answer: Because this is a reprint of a book that has already been published, and therefore was ineligible for new CIP.

Theoretically, if you request and receive a PCN, you can run it on your copyright page as above. When users punch this number into the Library of Congress, it will turn up the book’s record. Yep, there it is. In theory, your book will come out with the PCN on the copyright page and, when it is widely acquired by libraries, LoC will go to catalog it and they will see that it already has a control number so they will simply add the bibliographic information to the existing record.

In summary, if you want an LCCN for a book you are self-publishing, your best bet is to go through the PCN application to get one and run it on your copyright page. There is no need to go through this process unless you realistically believe your book will be acquired by libraries and you want to facilitate them in cataloging your title. This is distinct from wanting your book to be in libraries. The control number will not lead to helpful bibliographic data unless someone at LoC catalogs your book. Otherwise the PCN will just lead to a mostly blank record.

The last important thing to know about CIP data, LCCNs, and PCNs, is that none of these things establish copyright ownership nor do they assist you in proving your ownership of copyright should it ever be contested in court. The CIP program, and the cataloging program generally, at the Library of Congress have nothing to do with copyright. They are completely distinct. Unrelated. The good catalogers at the Library of Congress do not care about your copyright.

TL;DR: Skip the CIP.

I’ll talk all about copyright, copyright registration, the Copyright Office, and my good friend Form TX, in Thursday’s article. Enjoy your cicada screams while they’re here, local friends. Their days are numbered.

If you have questions that you'd like to see answered in Shelf Life, ideas for topics that you'd like to explore, or feedback on the newsletter, please feel free to contact me. I would love to hear from you.

For more information about who I am, what I do, and, most important, what my dog looks like, please visit my website.

After you have read a few posts, if you find that you're enjoying Shelf Life, please recommend it to your word-oriented friends.