New month, new Shelf: Shelf Life is now about video games. That is, video game. Tetris. The ultimate video game. I’m just kidding, there will be writing-related content if you stick with it. But first you’ll have to read about Tetris.

My partner just walked in on me “writing Shelf Life” but I was playing Tetris. I was conducting research. I got a score of 71,000-odd points. I don’t know what that means in the grand scheme of Tetris. I have to assume it was a bad score. My word processor now looks bleak by comparison. I will see falling blocks in my dreams tonight.

Here is a link where you can play some Tetris, for free, in your web browser.

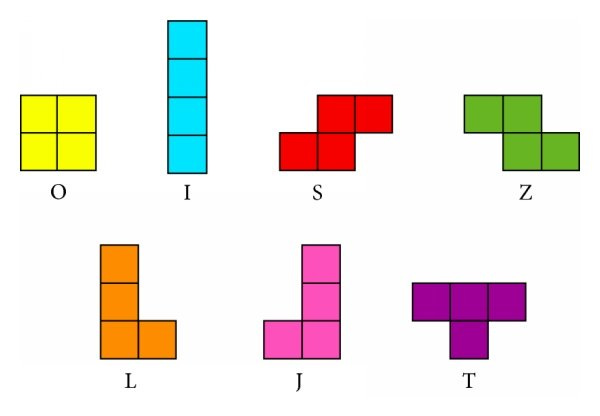

Tetris is a game where seven shapes—called tetrominoes, each made from a different configuration of four square blocks—fall from the top of the screen toward the bottom. The player rotates the tetrominoes as they fall and arranges them at the bottom of the screen so they form a solid wall with no gaps. Completed horizontal rows disappear and the rows above drop down, freeing more room at the top of the screen. When the piled blocks reach the top of the screen, the player loses.

Note: The player can never win. In his 1988 master’s thesis, “Can You Win at Tetris?” John Brzustowski posits that “winning” might look like a game that goes on indefinitely—one in which the player never loses but keeps clearing rows forever. To test his thesis, Brzustowski had a sample of Tetris players (N = 24) rank the seven tetrominoes according to the difficulty of placing them. He found that the pieces are not all equally easy to place, with the “right kink” (Z) and “left kink” (S) pieces hardest to play. Given that the sequence of dropping pieces is random, and that in a long enough random sequence you will eventually, inevitably, get a string of hard-to-play tetrominoes that can’t form solid lines (or enough solid lines to clear the board faster than the pieces are dropping), the player will always, eventually, lose.

Writing feels like this. You can never win, you just try to delay losing for as long as possible. There is always more to write. Try to stay alive and keep writing. It’s just like Tetris.

However—although Tetris is a single-player game—you can win at Tetris against other players also playing Tetris, by outscoring the other player or reaching an agreed score faster than them. Tetris 99 pits 99 players against one another to see who can play longest before losing. In-person Tetris competitions, naturally, are also a thing. In fact if you feel like reading two articles on Tetris today, go check out Chris Higgins’s article “Playing to Lose” after you finish this.

Although it’s a video game, I don’t think of Tetris like I think of Super Mario Brothers or The Legend of Zelda. Rather, I think of Tetris like checkers or go, a simple game with infinite replayability that humans will probably still enjoy playing 100 years from now. The Shannon Number, 10120, represents the possible combinations for a typical game of chess lasting about 40 pairs of moves. To put that in context, there are believed to be anywhere from 1078 to 1080 atoms in the observable universe.

Meanwhile, there are “7! * 7 * 6 possible combinations (211680)” of the first 9 tetrominoes to drop in a given game of Tetris. That’s the first 9 pieces. A quick game of Tetris might drop 180 pieces per minute. Anyway what I’m getting at is, if we’re not bored yet with 6 unique pieces on a 64-square board after 1,500 years, we’re not likely to get bored with Tetris’s 7 unique pieces on an 200-square board any quicker.

The final cool thing I’ll mention about Tetris is the Tetris effect, or the propensity of Tetris to alter “thoughts, dreams, and other experiences not directly linked to said activity” of players who dedicate substantial time to it. This is noteworthy because the Tetris effect can be utilized to prevent or mitigate the symptoms of PTSD when a person plays Tetris following a traumatic event.

All of the above is to discuss how cool and great Tetris is. It’s a giant among video games, maybe among games generally. At its core, it is a game about different-shaped blocks falling from the heavens and finding the right place to slot them into terra firma. It’s a game of visualizing the positive space you are about to receive and the negative space you already have and fitting them together the best you can.

I have been thinking a lot about Tetris because I have also been working on the plotting of a few stories and it’s an eerily similar experience. Ideas are dropping from above while I grab them, spin them around, and try to find the place where they best fit into the stories I have that need parts.

So I asked myself: Can you apply Tetris strategies for plotting and, if so, what are the best Tetri strategies? So let’s circle back to Brzustowski’s master’s thesis—to which I assume you clicked through and read the whole thing, because it’s fascinating. As part of his player survey, Brzustowski asked his 24 respondents:

If you wanted to help a beginning Tetris player, and could give only one simple piece of advice to that player, what would it be?

Play pieces as low as possible.

Try not to leave any holes.

If you can clear a row, do it.

Watch to see what piece will come next.

Play pieces of the same type close to one another.

Respondents (N = 24) selected “Try not to leave any holes” the most (n = 8) followed by “If you can clear a row, do it” (n = 5); then “Play pieces as low as possible” (n = 3); then “Watch to see what piece will come next” (n = 2). No respondents selected “Play pieces of the same type close to one another.” Seven respondents elected to write in their own advice. The respondent-written advice as shared in section 6.2 include:

Stay calm.

Leave a space by the wall for a tetris (ie, a simultaneous clearing of four rows using the I shape).

Don’t wait for the perfect piece.

Pretend you are having sex.

That last could be a joke answer, but it might be someone’s real Tetris strategy. We will never know because, I reiterate, this research is from 1988. I’m going to disregard that answer, as well as “Watch to see what piece will come next”—because you can do that in Tetris but not in brainstorming—and “Play pieces of the same type close to one another,” because no one recommended that advice.

Play Pieces as Low as Possible

Put another way, slot the pieces you receive into the puzzle at the most foundational level into which they can fit. Verdict? Solid writing advice. Never introduce in Chapter 10 a character who could have been introduced in Chapter 2. If your hero needs to claim the Magical Sword of Slaying during the climax, it should have been introduced during the exposition and referenced again during the rising action. Wherever you may be in drafting a story, stop and consider where a new idea might best be slotted into the draft. It might not be on the page you’re writing right now. It might be way back at the beginning.

Try Not to Leave Any Holes

Every reader hates plot holes. If you introduce a noun—a person, place, thing, or idea—make sure you outroduce it before the end of the manuscript. Or hint that this noun’s story carries on in the next volume. Don’t leave dangling elements and loose ends.

If You Can Clear a Line, Do It

Clearing a line means creating a perfectly solid row with no holes; filling any existing holes so the line becomes complete, thus disappearing from the field. Completion grants momentum. (Although in Tetris it just rewards you with faster-dropping tetrominoes.) When you need a win, find a line you can clear. Complete a scene, a chapter, a dialogue exchange, or even a clever epigraph for a chapter or part. I find it helpful, myself, never to leave off writing at the end of a session midway through a paragraph. If I do, it’s harder for me to start up again for some reason. Clear the sentence, paragraph, scene, or chapter if you can. Nothing motivates me like checking something off a list.

Leave Space for a Tetris

Put another way: Leave space for a slam dunk. For a surprise, a twist—the unexpected (even to you, the author). In writing this might mean leaving some aspects of the work unplanned to encourage you to think them up on the fly, or it might mean allowing yourself the flexibility to change something you planned into something better instead of hewing faithfully to all your initial plans. Stories grow in the telling. Let them.

Don’t Wait for the Perfect Piece

Best writing advice: “Don’t wait for inspiration to strike, just get writing.” Don’t wait for the perfect idea to come along, discarding the bounty of slightly imperfect ideas falling into your brain. If an idea is truly not well-suited for whatever you’re writing, then stash it in your idea bucket. Put everything plausible in the maybe pile for your current project—you can always punt them to the idea bucket later. Don’t discard an idea that doesn’t appeal or work well on first consideration. Sometimes ideas need a little time to work on your brain. Go ahead and slot these maybes into your story somewhere and see how they fit. Worst case scenario, you can always take them out again. It’s not like they’ll pile up to the top of the playing field and end the game.

Stay Calm

Everything written can be revised and changed. The first draft doesn’t have to be good. An idea can never be “wasted” or “used up.” Don’t psyche yourself out.

If you have questions that you'd like to see answered in Shelf Life, ideas for topics that you'd like to explore, or feedback on the newsletter, please feel free to contact me. I would love to hear from you.

For more information about who I am, what I do, and, most important, what my dog looks like, please visit my website.

After you have read a few posts, if you find that you're enjoying Shelf Life, please recommend it to your word-oriented friends.