A lovely friend, who spent several years as an editorial freelancer manager, received weekly queries seeking freelance proofreading jobs from applicants with no concrete qualifications for the position other than the ability to read. Don’t get me wrong! Being able to read is a good start.

She’d send out a test to all prospective proofers along with a request for their experience, if any. And if none, then some thoughts on why they would be a good fit for this type of work. The answer that came back more than any other by a large margin—“I spot typos on restaurant menus all the time.” Needless to say, she has a large rolodex of ready candidates for the day she goes into business publishing menus.

Our company did not publish menus.

Anyone can spot a typo in a menu, an advertisement, a sign. A proofreader can read menu entries for three hours straight without their attention wavering or straying. Proofreading isn’t like regular reading. You have to be able to keep your attention on the words without becoming absorbed in whatever they say. You have to read them for sense without letting them engross you.

You also have to keep your eyes peeled for page formatting errors and tiny typographic mistakes. The more you engage with whatever you’re reading, the more glaring an error has to be for you to notice it. Most readers will notice an outright misspelling even if they’re absorbed in the text. How many notice a quotation mark turned the wrong way? How many catch the common OCR error that substitutes “rn” for “m”? How many can reliably spot a comma that is italicized when it shouldn’t be?

Authors of any type of writing will have to look at proofs eventually. Either you’re publishing traditionally and you’ll receive a proof from your publisher, or you’re self publishing and you’ll get a proof directly from whoever is doing your typesetting.

If you’re working with a publisher, they probably have someone in a professional capacity also reviewing your proofs. For books that’s usually a professional proofreader—sometimes two proofreaders whose work will be compared to make doubly sure nothing was missed—while for shorter publications like journal articles it’s sometimes a production editor. Crucially, someone who knows how to proofread likely reviews your proofs. If that’s the case, then you as the author need only do a high-level review for egregious errors.

If you’re self-publishing, and especially if you’ve already shelled out money for earlier professionals like development editors and copyeditors, you might not have funds for a professional proofreader—so you’re on the hook to catch everything all by yourself.

What if you’re publishing an e-book only? Proofs usually refers to the formatted PDF that ultimately goes to the printer to create your book. If you’re only publishing an electronic copy of your book in a reflowable format like EPUB, you won’t have a proof to review. You should still make sure you proofread your final output file before you upload it for sale: Errors that weren’t caught in your manuscript before conversion to EPUB will still be in there, and new errors (especially formatting errors) may have crept in during conversion. Don’t assume that a perfect manuscript file sent out for conversion will return a perfect e-reader file.

You’re just going to have to read some proofs. Today I’ll cover how to do this when working with a pro, how to handle this when flying solo, and how to proof an e-reader file.

Proofing Basics

The first thing to know is that there is an agreed-upon set of proofreader marks that editors and compositors all recognize. You can find some of the basic ones here but there are more. You will almost certainly not need to use these marks because proof markup is done electronically these days: Either on a PDF, using the commenting markup tools included with the free edition of Acrobat Reader, or in an XML-driven text editor. I don’t know of any publisher that still encourages hardcopy proof markup. If for some wild reason you need to mark your corrections with a pencil on a printed copy of your proof, you should use those marks when you can—any compositor who knows the business will interpret them correctly. Use a red or dark green pencil!

In proofreading, the hash sign “#” universally means “space”; “rom” means “set Roman” (ie, remove boldface, italics, and underlining); “t/o” is short for “throughout” (ie, the marked change should be made in all instances of the same thing, like a typo in a running head); and “stet” is a contraction of “let this stand as it was set” (meaning, do not make the correction someone else has marked here).

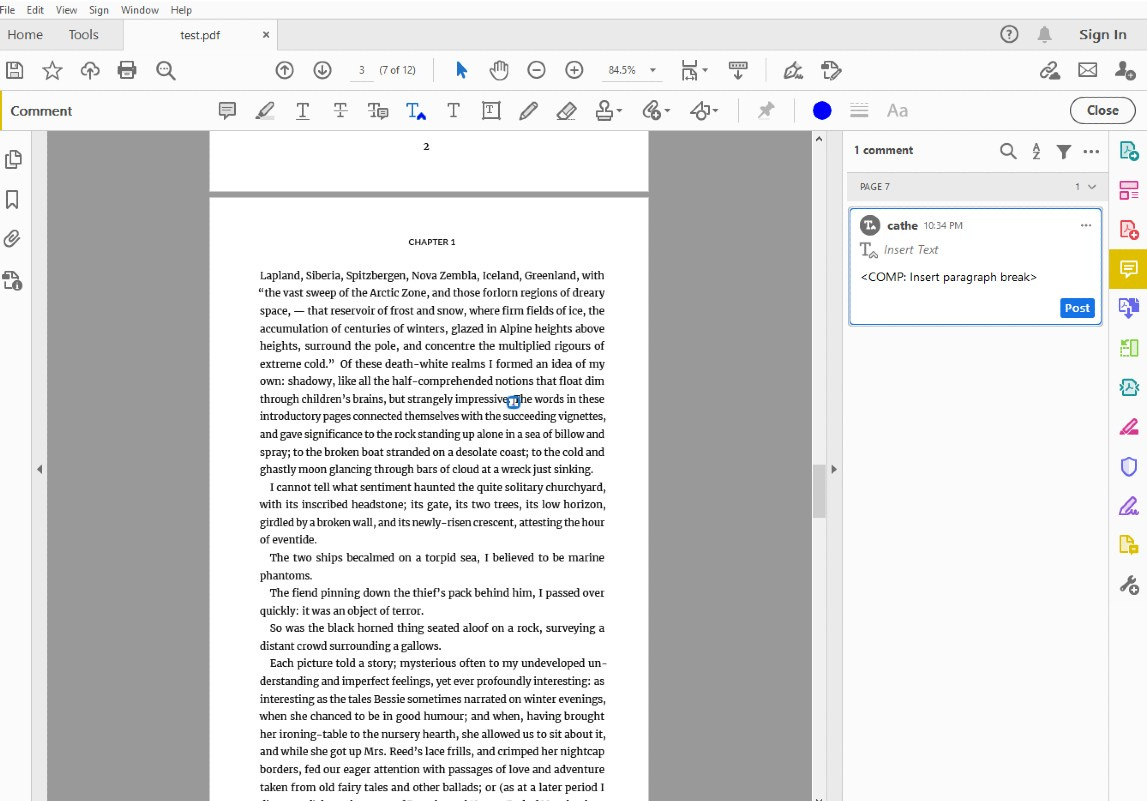

If you are marking your proof electronically in PDF format, your publisher probably sent instructions on exactly how to do that, which you should follow. If they didn’t give instructions or if you’re working directly with a compositor you have hired, the best way to make sure your corrections are understood is to strike out the text that is wrong and replace it with the text that is correct. Don’t describe the change and don’t put the correct text somewhere nearby using the comment feature. Do it like this:

If you need to give an instruction to the compositor, put that part in angle brackets to indicate that the text you are writing should not be inserted verbatim and is an instruction:

Compositors are not unintelligent but they are trained to take proof corrections literally. If you make a typo in a proof correction, that typo’s going in your book. The compositor’s job is not to correct your mistakes. Be explicit to minimize questions and proof rounds.

If you believe a mistake on your proof was inserted during the typesetting process—for instance if a chapter was omitted, the line spacing is wrong, a paragraph is all in the wrong font, or something like that—then you should mark this correction as a “printer error” using the shorthand “PE” (and put it in angle brackets, like an instruction). This tells the compositor that you should not be charged for this alteration, because it is being requested to fix their error. (If you’re not paying for corrections because your composition package includes infinite alterations or because your publisher is paying, then you don’t need to worry about marking PEs).

Make sure you understand how your compositor charges for alterations if you’re paying out of pocket. Many compositors charge by the correction so if a sentence contains multiple errors you’re better off replacing the whole sentence than marking each error separately.

Proofs may contain queries from the publisher or the copyeditor that need to be answered before publication. Proof queries can appear a lot of ways, but usually they’re encoded so in text or in the margin you’ll see a note like “AU1” or “Q1” that corresponds to question number one on your query list. A fun fact about proof queries is that if you don’t answer them I have to call you to get the answer, which delays your publication but also, listen, I hate the telephone, we all hate the telephone. Please answer your queries. All queries matter.

Proofing in Good Company

If you’re working alongside a professional proofreader, you don’t need to be as vigilant as you otherwise might. A proofreader can be relied upon to catch spelling errors, typos, and formatting errors; to adjust punctuation and grammar to conform to style; and to query any sentences that may need to be recast for clarity. The proofreader will not make any substantive changes without querying—they will not quietly make any changes that could affect the meaning of what you have written.

This leaves you free to read your manuscript through one last time. If you spot any of the abovementioned stuff, you should mark it—even a great proofreader misses an error sometimes. Primarily, though, you should focus on the items only the author can catch: Content errors. Although this is not a time for wordsmithing or rewriting, it is your last opportunity to make changes before the project publishes, so make sure there aren’t any factual errors.

If you had an opportunity to work with your copyeditor directly, or to review the copyeditor’s redlines, or even to answer queries from the copyediting stage, now is the time to verify that your requests were carried out faithfully and query answers interpreted and implemented correctly. If you requested changes from the copyeditor be stetted, for example, make sure that your original text was left intact and has been set in proofs without the copyeditor’s changes.

Proofing Solo

If you’re self-publishing and nobody’s going to be reading these proofs for you, then you need to handle everything from the previous section plus some more.

A professional proofreader would look for misspelled words, grammatical errors, and errors of punctuation, first of all. Hopefully, if you are self-publishing, you have caught most or all of these in previous rounds of manuscript review. If you have overlooked an error in all previous stages, you might still catch it now—sometimes typos only become obvious when you see them on the laid-out page. Make sure you mark all of these.

A pro would also correct layout errors, so you’ll have to be responsible for those as well. I’ll include a list here of the most common ones and what to look for. Check each page or spread for all of these items:

Folio placement and consecutive numbering—make sure the page number is placed in the correct spot on every page. If page numbers are in the corners, make sure odd numbers are on recto (right) pages and appear in the outer (right) corner, and even numbers are on verso (left) pages and appear in the outer (left) corner. Make sure page numbers are consecutive.

Blind folios are pages that are counted in the pagination of the book but do not have a visible page number on them—like the blank pages between chapters or a page that is fully taken up by a photo. These still count as a page so make sure the next numbered page picks up with the correct page number.

Format of all chapter-opening pages matches exactly (for example, “Chapter One” shouldn’t be followed by “2”).

Text block placement—ensure that the text block is the same size on every spread. The top line of the verso and recto pages in a single spread should align horizontally, as should the bottom lines of the spread.

Loose or tight leading (line spacing); kerning (letter spacing); and word spacing—compositors make minor adjustments to all three to get the text blocks to fit neatly on each page without leaving widows or orphans, but these changes should not be noticeable except to someone who is measuring. If you see text that looks loose or tight enough to distract a reader, mark it for adjustment.

Hyphen stacks—your text will have been auto-hyphenated by the compositor to form a justified text block, but three lines that end with a hyphen is the maximum you should have in a row. If you see four or more, ask the compositor to fix.

Incorrect auto-hyphenation—words that are hyphenated to cause them to wrap to the next line are broken according to a complex set of rules but the simplest version is, they should be broken between syllables according to the dictionary you and the compositor are both using. Words should never be hyphenated in the middle of a syllable, and they should never be hyphenated so that they break with one letter separated from the rest of the word.

Finally, there are some elements of a book that a pro would check a couple of times, and that someone at your publisher would be checking as well, because they are just that important. If you’re on your own, make sure you double, triple, quadruple check the following:

The title of your book is complete and spelled correctly in every place it appears (you should not have Pride and Prejudice in one place and Pride & Prejudice in another).

Your name is spelled correctly and styled the same way everywhere it appears (you don’t want to be John Q. Public in one spot, John Public in another spot, J.Q. Public in a third spot, and so on).

ISBN is correct on the copyright page and anywhere else it appears. Don’t check it against an earlier proof or the mockup copyright page you sent the compositor—go back to your receipt of purchase and verify it numeral by numeral.

Running heads are placed correctly (verso and recto) with no typos on any page. You’d think if it’s correct once it’d be correct in every instance but I’ve seen these go awry. Check them all.

Pagination is correct and consecutive from start to end (check it again).

All parts and chapters are present and in the correct order.

If possible, have a second reader check your proof. Make sure you’re clear that they shouldn’t be offering story feedback or language suggestions, but only checking spelling, grammar, punctuation, and formatting. A fresh set of eyes never fails to catch something you’ve missed.

Proofing an EPUB

If you’re proofing a file that is intended for upload to an e-reader (EPUB, MOBI, AZW, etc), you will not have to check for most of the formatting items above because the text is inherently reflowable; the pagination; font face, font size, line spacing, and other formatting parameters can be changed by the end user at any time. That said, the conversion of manuscript (or PDF) to these e-reader file formats can introduce a whole different slew of errors that you’d be wise to check for.

Again, as in every proofread, read one last time to look for misspellings, grammatical errors, punctuation mistakes, and content errors. But in addition to those, make sure you’re looking out for:

Hyphens gone wild—if you had auto-hyphenation turned on in the file you converted from, the e-reader may interpret all those soft hyphens as regular hyphens and insert them in words that no longer fall at the end of a line. If you see hyphens all over the place, this is probably what happened. Turn off your manuscript’s auto-hyph functionality and convert again.

Text formatting drop out—italics, bold face, underlining, small caps, those kinds of things can drop out during the conversion process. If formatting drops, the best way to get it all back in is to compare your final manuscript or proof (whatever file you converted from) visually with the e-reader file and manually fix each one.

Special character drop out—as in the previous bullet, special characters can drop out. By special characters I mean ligatures; letters with diacritics like é and ç; symbols that don’t appear on a standard keyboard like the trademark or copyright signs; stacked fractions; Greek letters; mathtype; and so on. If you know your manuscript has any of these, check the e-reader file to make sure they converted correctly.

Line and paragraph breaking—ensure that stray hard returns haven’t cropped up in the conversion, breaking your lines or paragraphs in weird places.

Metadata—check that your book’s metadata imported correctly (if you converted the file yourself) or that whoever performed your file conversion entered them correctly. ISBN, title, author name, publication date, subject category, and so on, should all be correct and exactly match every other instance of the same data.

According to the Editorial Freelancers Association’s 2020 Rate Chart, professional proofreading costs about $0.02 to $0.029 per word. For a manuscript of around 80,000 words, that’s a fair chunk of change. That’s on the very high side of proofreading rates that I have seen and EFA members are the gold standard. You can find affordable proofreading on Reedsy for about half that.

Whether you’re on your own or working with some proofing pals, make sure you read carefully, take frequent breaks to avoid getting caught up in the story, and take a step backward to squint at each page to confirm it looks visually correct. When you think you’re done, ask Adobe Acrobat to show your PDF in spread view (View > Two Page View + Show Cover Page in Single View) and go through it one last time in spread view.

You’re almost at the finish line. Don’t quit now.

Hey, I’m off to get my second COVID jab so there’s a small chance you’ll get a low-effort Shelf Life on Thursday if I feel crummy. Fair warning. I’ll do the best I can to get you a high-quality article but there’s a 50/50 chance you get a fever-dream inspired screed on reflex blue instead.

If you have questions that you'd like to see answered in Shelf Life, ideas for topics that you'd like to explore, or feedback on the newsletter, please feel free to contact me. I would love to hear from you.

For more information about who I am, what I do, and, most important, what my dog looks like, please visit my website.

After you have read a few posts, if you find that you're enjoying Shelf Life, please recommend it to your word-oriented friends.