Order of Operations

For Editorial Services

First, wishing a happy May the Fourth to those who celebrate (Star Wars fans) and then, tomorrow, a happy Cinco de Mayo to those who celebrate (everyone). Did you know that only once every 7,000 years do Cinco de Mayo and Saint Patrick’s Day both fall on a Friday? The ancient Mayans predicted this would happen one day in the far future and named this occurrence Drinkapalooza. Abraham Lincoln expressed, in some of his letters to Mary Todd Lincoln, a terrible sorrow that Drinkapalooza would not happen in his lifetime.

What a time to be alive, friends. I don’t actually drink, but ten-years-younger Catherine would die of alcohol poisoning under these circumstances.

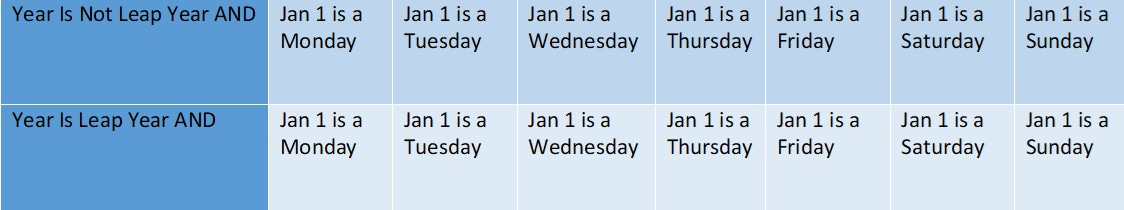

Listen, whenever someone tells you it’s been hundreds or thousands of years since a certain configuration on the Gregorian calendar has come around, remind yourself there are only 14 possible calendar configurations. This table can help you visualize it:

The calendar repeats every 28 years. It’s never been more than 28 years since any particular combination of date and day. Also, since there are exactly 49 days between March 17 and May 5 even when it is a leap year, Saint Patrick’s Day and Cinco De Mayo always happen on the same day of the week. That day is a Friday as often as it is any other day of the week.

And that is why we don’t believe everything we read in a meme.

Onward.

Today I want to talk about the order of operations. That’s why I did all that fun calendar math above. Get it? This is Math Life. Remember PEMDAS, or Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally, from elementary school math? That was how to remember to do the mathematical operations in the correct order:

Parentheses

Exponents

Multiplication

Division

Algebra

Sucks

I don’t know, I’m not good at math. I have a learning disability. The point is you have to do any operations inside parentheses before you do any operations outside parentheses, and you have to do any multiplication in the equation before you do any division, otherwise your answer will come out wrong.

I mean that’s one reason why your answer might come out wrong. I personally find there are infinite reasons why your answer might come out wrong.

Pure mathematics never really does it for me so I like to talk about the order of operations in terms of building a house.

Lay the foundation.

Frame the house.

Put on the roof.

Put in the floors.

Put in the plumbing and electric.

Put on the drywall.

Apply finishes to the walls and floors, like paint, wallpaper, carpet, tile.

Install fixtures like cabinets, counters, sinks, appliances.

You can’t do these operations in the wrong order. You can’t paint a wall if there’s no wall. You could paint the frame, but what would be the point of that? What if somebody decided to build a house and they had the painters come in to paint before the drywall got installed? Let’s say the painters are really determined so they paint what’s there. Then they have to come back and paint again after the drywall goes up.

Here’s a fun story about house painting: I dated a dumb but beautiful man back in the 1990s and he was a subcontractor working on houses and he got hired to paint the interior of some new construction. I was skipping school and helping him with it and he ran low on paint so he gave me some cash and told me to go to Home Depot and get some white Duron paint.

I asked him, “What shade of white Duron paint, though?”

And he looked at me like I was the dumb but beautiful one and said, “It doesn’t matter, white paint is white paint. It’s all exactly the same.”

Long story short, he got fired for painting the inside of the house two different shades of white, and I’m beautiful but I’m not dumb.

There’s an order of operations for editing books, too. That’s what today’s Shelf Life is actually about. Obviously, you can’t revise or edit a manuscript you haven’t written yet. That’s equivalent to going in to paint the walls and finding there are no walls to paint. That’s obvious to anyone; you can’t do this operation before that one because it’s not possible.

But there are also the operations that can be done out of order—literally, it’s possible—but it’s inadvisable because you won’t be able to do earlier or later operations well, or you’ll have to re-do operations that you’ve already done.

Example in construction: You install the cabinets in the kitchen before painting the walls. Does this ruin everything? No. Do you do as good a job painting after the cabinets go in as you would have before they went in? Arguable. Do you run the risk of ruining the new cabinets with paint? Yes.

Another example: Installing the carpet before you install the carpet pad. You can’t just install the carpet pad after you’ve installed the carpet; the pad has to be underneath. Now your choices are:

Rip up the carpet, install the pad, and install new carpet.

Forgo the carpet pad; just don’t install it. It’s too late.

Either choice, at that point, either outcome, is a bad one.

Getting back to the idea that you can’t edit a manuscript if the manuscript doesn’t exist: I’ll be honest with you. I’ve often been asked if I will edit manuscripts that don’t yet exist. Now: People aren’t dumb—mostly. They don’t really think I can edit a manuscript they haven’t yet written. It’s more like that they want to secure my services in advance, or at least know that they can, before they start writing. The conversation, anecdotally, goes like this:

Them: Can you edit my YA science fiction manuscript?

Me: Tell me more about your manuscript, how many words? When do you need it done?

Them: Oh I haven’t written it yet.

Still, I can’t make an editorial commitment until a manuscript is actually complete; I need critical information like volume of content and deadline to figure out if I can do it. You can’t reasonably buy carpet for a house if no one knows yet how many square feet will need to be carpeted. I mean, you can, but you’re almost certainly not going to end up with the right amount of carpet and resources are definitely going to be wasted when you overbuy or underbuy and have to go back for more.

But another conversation, anecdotally, goes like this:

Them: Can you proofread my book?

Me: How many pages? What’s the deadline? Do you have the editor’s style sheet for me to use?

Them: I want you to proofread it first before I send it to my editor.

Alarm bells. Someone’s trying to install carpeting but they haven’t got the carpet pad down yet.

In the order of publishing operations, proofreading has to happen after all other editing concludes. Proofreading is done using the proof pages after composition (ie, not the manuscript); composition is expensive and making text changes after composition is very expensive. Therefore, making major editorial changes after proof composition is a cost-prohibitive and ineffective way to edit.

Proofreading is intended to detect errors that occurred during creation of the proofs (composition) and assumes the manuscript that was sent to comp was near perfectly clean from prior rounds of editing. While there may be a typo here or there that was missed by all the previous editors, for the most part a proofreader will find very little in the way of editorial oversight and will mostly find errors created by composition—formatting errors, pagination and folio errors, hyphen stacks, wrong fonts, dropped characters.

Because the proofreader expects to read for different things than an editor, the going rate for proofreading is typically much lower than the rate for editing. It is a different service. An author cannot ask for proofreading and expect to pay for proofreading but expect to get editing. Further, the proofreader cannot do a good job if they’re reading dirty proof that hasn’t been through editing. Their job is to scrutinize and find the last few things that everyone else has missed. They can’t do that job if they’re reading proof with typos and grammatical errors on every page.

Before I get to the proper order of editorial operations, one more thing. Not every manuscript needs every level of editing; in fact, most don’t. If a manuscript truly does not need a certain level of work, there is no point putting the manuscript through that type of edit and paying for it. However: A later stage of editorial operation cannot be expected to do the work leftover from an earlier stage that was skipped.

Let me put it like this: If a manuscript truly does not need a developmental edit, then do not hire a developmental editor for that manuscript. However, you do not then ask the copyeditor to look for developmental items, make recommendations of that nature, or propose changes.

Herewith, your order of editorial operations:

Developmental (or structural) edit.

Line edit.

Copyedit.

Proof composition.

Proofread.

A developmental edit takes a high-level, big-picture look at the manuscript and makes edits and recommendations for changes for things like structure, story flow, character development, events occurring out of chronology, plot holes, and so on. In a nonfiction book, a developmental editor will likely do some analysis of your book’s intended competition and ensure that your manuscript contains everything it needs to compete, and recommend additions or deletions to improve marketability. With fiction, a developmental editor can make recommendations to help with characters who feel a bit flat, dialogue or action that doesn’t feel realistic, plot developments or resolutions that are unsatisfying, and more.

The developmental editor is not looking for grammar, spelling errors, typos, and formatting errors. There is no reason to make changes to any of those things at the development stage because the author will have to go in and revise sections per the developmental editor’s feedback.

A line edit is the next-most comprehensive edit but takes a closer look at the text than a developmental edit. A line editor will read the manuscript, going sentence by sentence and making recommendations to improve the use of language, text and idea flow, structure, and so on. They will also be looking for items like repeated text (you would be surprised how many writers accidentally reuse the same snippet of text more than once!), disorganized text, clarity and confusing sentences, and generally making sure the text is as clear and concise as it can be, without disrupting the author’s voice.

The line editor will likely fix a lot of grammar and spelling errors along the way as they notice them, but will probably not impose manual style on the text.

A copyedit is the edit people tend to think of as “editing,” in my experience. This is the person whose job it is to take a style manual and a dictionary and impose style and consistency across the whole manuscript. This editor will ensure your grammar is correct and consistent; for instance, that you use or omit the serial comma consistently, rather than using it sometimes and sometimes not. They will ensure your spelling is correct and, again, consistent. Spelling is not always a right/wrong prospect: They will make sure you’re using forgo and forego in the correct spots based on context, that you’re correctly using toward or towards depending on what variation of English you’re using, and so on. If your manuscript has references (endnotes or footnotes), the copyeditor will do a thorough review of those as well.

After copyediting, a manuscript is generally considered editorially final. At this point, the manuscript will be sent to composition so it can be set into book pages with running heads, running feet, a table of contents, pagination, margins, and all that good stuff.

After page comp, the proofread is the final quality check. The proofreader checks for proof formatting consistency: Chapter numbers and titles formatted correctly, folios and running heads, page numbers on the table of contents are correct, copyright page set correctly, margins the correct size and consistent throughout. They will also read the text to look for any lingering typos or errors as well as any mistakes that may have been introduced by the proof composition process, like character conversion errors.

Since the author does not usually review the proofreader’s work, the proofreader does not make any substantive changes. If they notice something egregious, they might alert the author or the publisher they are working with about what they saw, but they will not attempt to correct anything unless it is obviously, unquestionably wrong. They will not make changes to impose consistent style unless minor; for example, if they notice one serial comma is missing when it has been used consistently everywhere else, they will likely put it in—but they will not go through the text and insert serial commas in dozens of places if it has been used or not used without explanation.

Finally: What about beta reads and sensitivity reads? Those are part of the author’s revision process and take place before the editorial process begins. They are part of finishing the manuscript so that editing can start.

If you have questions that you'd like to see answered in Shelf Life, ideas for topics that you'd like to explore, or feedback on the newsletter, please feel free to contact me. I would love to hear from you.

For more information about who I am, what I do, and, most important, what my dog looks like, please visit my website.

After you have read a few posts, if you find that you're enjoying Shelf Life, please recommend it to your word-oriented friends.

Hilarious! I can't imagine going to a home improvement store and getting base white paint, and we've tried! They simply won't let anyone buy a bucket without dripping in a bit of special color matching sauce and mixing it up for you.